Cholera disease - Symptoms, Types, Causes, Prevention, and Treatment

Cholera definition

Cholera is an acute gastrointestinal tract infection caused by the consumption (intake) of food and water contaminated with the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae (of serogroups O1 and O139). It is a highly contagious diarrheal disease (can spread quickly from person to person through direct, indirect, or droplet contact) that affects several people every year. Cholera toxins cause a massive outflow of electrolyte-rich fluid into the intestines, resulting in volume depletion (fluid losses due to vomiting, diarrhea, etc.) and shock and shock.

Most individuals affected by cholera do not show any symptoms. However, the bacteria are present in feces for 1 to 10 days after infection, contaminated the environment, thus affecting others. Some patients can develop watery diarrhea along with severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, which may become severe if left untreated.

Oral rehydration solution (ORS) is the primary treatment for cholera. Other treatment approaches include antibiotics and nutritional supplements, which have been proven to help reduce the duration and severity of symptoms.

Cholera meaning

Cholera is commonly termed “Haiza” in Hindi. The word cholera comes from the Greek word

chole, or the non-specific word

bile, which means flow of bile or bilious disease.

Cholera prevalence

Prevalence of cholera in the World

Researchers have estimated that every year, there are 13 to 40 lakh cases of cholera and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths worldwide because of cholera. Cholera exists as an endemic disease in nearly 47 less-developed countries, mainly in south and Southeast Asia and Africa. Its outbreaks are unusual in developed countries.

Prevalence of cholera in India

Cholera outbreaks are relatively common in India. The disease is endemic and has marked seasonal dynamics; it is prevalent in the hot, humid, and rainy seasons. 565 outbreaks reported between 2011 and 2020 led to 45,759 cases and 263 deaths because of cholera. Outbreaks occurred throughout the year but explodes with monsoons (June through September). In Tamil Nadu, a typical peak of cholera disease outbreaks was observed from December to January. 72% (33,089/45,759) of outbreak-related cases were reported in five states, namely Maharashtra, Punjab, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka.

The incidence of cholera cases was estimated to be 1.6 cases/1000 population per year, or 40/1000 cases of acute diarrhea in India. Surveillance data revealed a steady increase in reported cholera outbreaks all over the country. From 1997 to 2006 duration, 68 outbreaks were reported, while the reported outbreaks increased to 559 between 2009 and 2017.

Cholera types

Based on the spectrum, cholera is mainly divided into epidemic and endemic, which are as follows:

- Epidemic cholera: It is more severe and present in huge numbers simultaneously and across various age groups, as the whole population lacks pre-existing immunity.

- Endemic cholera: Small outbreaks reemerge seasonally, creating an anticholera immunity that serves as a protective factor in adults. Only children under five who lack immunity are at a greater risk of symptomatic illness.

Vibrio cholerae classification

Based on the structure of the O-antigen of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Vibrio cholerae is divided into more than 200 serogroups.

- Out of them, serogroups O1 and O139 (a subset of strains) can lead to cholera and their ability to produce toxins known as cholera toxin (CTX)

- Non-O1 and non-O139 (which are not O1 and O139 serogroups) usually lack the cholera toxin (CTX) and can lead to sporadic cases of bacteremia, wound infections, and outbreaks of small gastroenteritis but cannot cause cholera.

- Three serotypes, namely Inaba, Ogawa, and Hikojima (divisions of O1 strains), are grouped based on the methylation status of the terminal perosamine of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

- Classical and El Tor are the two biotypes of

V. cholerae O1 strains. They can be differentiated according to the phenotypic and genetic markers.

Cholera symptoms

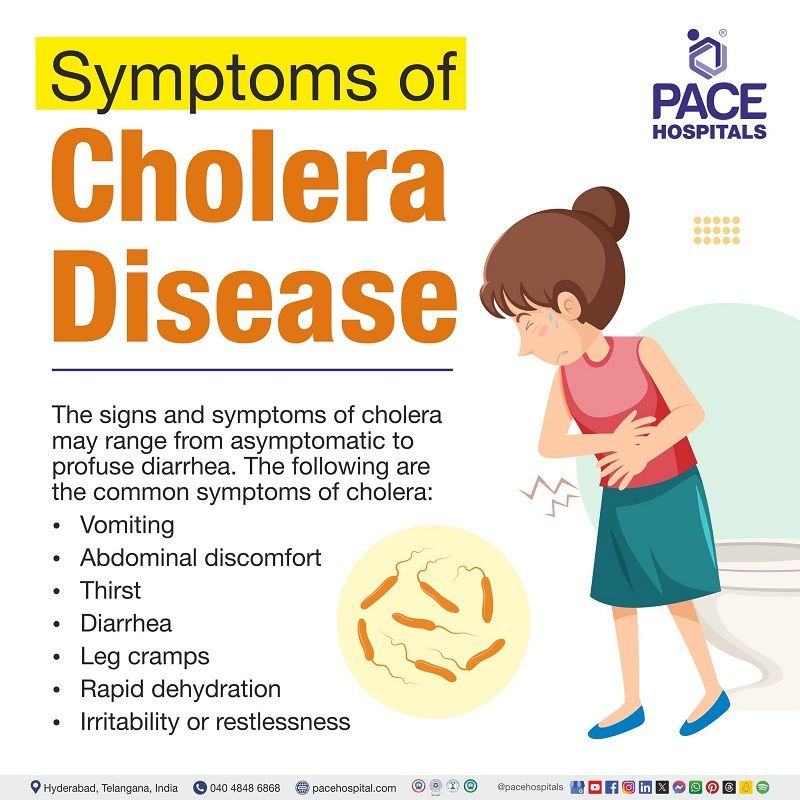

The signs and symptoms of cholera can range from asymptomatic (with no symptoms) to profuse diarrhea.

Common symptoms of cholera include:

- Vomiting

- Abdominal discomfort

- Thirst

- Diarrhea

- Leg cramps

- Rapid dehydration

- Irritability or restlessness

Other symptoms of cholera include:

- Other diarrheal illnesses can be differentiated clinically from severe cholera because of the profound and quick loss of fluid and electrolytes

- “Rice water” consistency stools can be seen in cholera patients that contain bile and mucus

- Cool skin, sunken eyes, lethargy, dry oral mucosa, low urine output, low blood pressure, wrinkled feet and hands, and decreased skin turgor(elasticity) can be seen because of hypovolemia (fluid loss)

- Lactic acidosis (buildup of lactic acid)

- Electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia (low blood potassium levels) and hypocalcemia (low blood calcium levels) can cause cramping and generalized muscle weakness

- Circulatory collapse (blood circulation is interrupted or reduced)

- Kussmaul breathing (quick, deep breathing at a consistent pace) may be seen because of acidosis from stool bicarbonate losses

- Severe hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) can be seen in children.

Risk factors of cholera

Individuals living in an unclean environment are more prone to cholera disease. Below are some factors that can increase the chance of getting cholera:

- Poverty: Cholera is generally termed as a disease of poverty. Economic development is an essential factor in cholera morbidity and mortality.

- Contaminated food and drinking water: According to a 2015 study published in BMC Public Health Journal, poor food preservation methods and eating roadside food were the independent risk factors for cholera.

- Overcrowding: A 2019 study published in the BMC Public Health Journal identified overcrowding and poor personal hygiene as risk factors for cholera.

- Prior vagotomy: It is a procedure that removes part of the vagus nerve.

- Use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and antihistamines: PPI and H2RA decrease the gastric acid content, leading to hypochlorhydria in people that can result in bacterial overgrowth in the gut, thus lowering protection against infections.

- Helicobacter pylori infection: H. Pylori infection was linked with a significant rise in the risk of life-threatening cholera, but only among individuals lacking natural vibriocidal immunity.

- Having type O blood: Though blood type O does not affect the risk of being infected with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, it significantly impacts the severity of the disease.

- Retinol deficiency: Retinol deficiency is associated with an increased risk of Vibrio cholerae infection and with a greater risk of symptomatic disease.

- Malnutrition: Malnutrition (lack of sufficient nutrients in the body) may damage the immune system, decrease gut barrier function, and allow Vibrio cholerae to grow vigorously, resulting in more severe symptomatic cholera.

- Living in or traveling to areas where cholera is present: Individuals living in or traveling to places where cholera is common are at a greater risk of contracting the disease.

Poor sanitation, female gender, disruption of water, sanitation systems, and gastrectomy are some of the other risk factors for cholera disease.

Vibrio cholerae causes

Cholera is an acute gastrointestinal tract infection caused by the consumption (intake) of food and water contaminated with the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae (of serogroups O1 and O139).

Mode of transmission of cholera: The common routes which could increase the risk of V. cholerae contamination in endemic areas include:

- Unimproved water sources

- Non-potable water

- Water pipeline leaks

- Open defecation

- Poor sanitation

- Poor hygiene

The causative agent of cholera: The causative organism of cholera is

vibrio cholerae

(highly motile, comma-shaped gram-negative bacteria with a single polar flagellum).

- Hundreds of serogroups that have pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains are present.

- Serogroups O1 and O139 (a subset of strains) can cause cholera until recent times.

- Contaminated food and water can cause cholera, mainly in the vulnerable communities that are affected by war, natural disasters, and famines.

- Cholera can spread by contact with the feces (poo) of a cholera-infected person.

Complications of cholera

No long-term complications have been found for cholera disease. But there are some complications that are quite common and can occur due to cholera:

- Hypovolemic shock: Cholera causes huge loss of fluid via diarrhea, reaching as high as 1 liter per hour in adults and 20 mL/kg per hour in children, thus causing severe volume depletion leading to hypovolemic shock.

- Metabolic acidosis: Metabolic acidosis in Asiatic cholera was caused by fecal loss of bicarbonate, with stool clearances of bicarbonate ranging up to 41 ml per minute.

- Acute tubular necrosis and renal failure: Dehydration, if left untreated, vomiting, and diarrhea may lead to isotonic dehydration, which can cause acute tubular necrosis and renal failure.

- Dehydration: Cholera is a potentially fatal diarrheal disease that results in large volumes of watery stool, leading to rapid dehydration

- Severe hypotension: Severe diarrhea in cholera can cause a decrease in blood pressure.

- Electrolyte abnormalities: Severe electrolyte imbalance can be seen in patients with cholera.

- Stroke: Severe hypotension (low blood pressure) can cause stroke, especially in elderly patients

- Aspiration pneumonia: Vomiting in cholera can cause aspiration pneumonia

- Cholera sicca: This unusual form of disease includes fluid accumulation in the intestinal lumen, an infrequent complication.

- Hypoglycemia: Decreased intake of food during acute illness may result in hypoglycemia, a lethal (dangerous) complication that is more frequent in children.

Miscarriages and premature deliveries in pregnant patients, chronic enteropathy, malnutrition, and, in some cases, even death are the other complications of cholera.

Cholera and diarrhoea difference

Cholera vs Diarrhoea

Diarrhea and cholera are both gastrointestinal conditions. However, diarrhoea is a classic symptom of cholera; even though they appear similar, they have the following differences:

| Parameters | Cholera | Diarrahea |

|---|---|---|

| What it is? | An infectious disease | A symptom which can be seen in various diseases and disorders |

| Caused by | Vibrio cholerae bacteria | Various viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections, medications, food intolerances, digestive disorders, stress, or dietary changes etc |

| Symptoms | Some of the symptoms may include thirst, vomiting, profuse watery diarrhea, vomiting, leg cramps, and restlessness. | The main symptom of this condition is passing loose, watery stools three or more times per day according to the severity. Loss of control of bowel movements, and urgency in needing washroom. pain in the abdomen may be seen. |

| Complications | Acute tubular necrosis and renal failure, dehydration, severe hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, stroke, aspiration pneumonia, cholera sicca, hypoglycemia | Dehydration, and electrolyte abnormalities are the common complications. They may increase depending on the disease type. |

| Treatment | Combination of oral rehydration therapy + antibiotic therapy. | Oral rehydration therapy is enough to treat diarrhea. Additional therapeutic venture is necessary to treat the condition causing diarrhea. |

Cholera prevention and control

Using different methods and strategies is the key to prevent, control, and decrease the number of deaths from cholera. Here are the following measures:

- Improved water, sanitation, and hygienic services: Economic development (using safe water and good hygienic practices) is one long-term solution for preventing cholera.

- Use of oral cholera vaccines (OCVs): Protection against cholera appears to continue for up to two years following a single dose of vaccine and for three to four years with an annual (yearly) booster.

- Surveillance: Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) can be valuable tools to detect outbreaks of cholera disease; nevertheless, to confirm the diagnosis, stool samples are sent to a laboratory for confirmation of Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139 by culture or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

- Sewage and fecal sludge management: In areas affected by cholera, fecal sludge (a mixture of human excreta, water, and solid waste) and sewage must be treated and managed effectively.

- Disinfection: Materials that may come in contact with the cholera patients need to be washed in hot water; if possible, chlorine bleach can be applied.

- Raising public awareness: Measures can be taken to increase awareness of cholera among people.

- Other measures: Using boiled or chlorinated water and avoiding uncooked vegetables and undercooked shellfish can prevent cholera.

Cholera diagnosis

The diagnosis of cholera is commonly based on clinical signs and symptoms in areas where laboratory facilities are not available. However, below are the tests involved in diagnosing cholera in developed laboratory settings:

- Stool or rectal swab culture (gold-standard reference method)

- Biochemical tests such as sero grouping and serotyping with specific antibodies

- Blood tests such as serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine should be measured

- Urine tests to evaluate dehydration

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) to identify the O1 or O130 antigen in stool samples.

- Rapid LAMP-based Diagnostic Test (RLDT); a simple, rapid, and sensitive diagnostic assay.

- Rapid dipstick test

- Darkfield microscopy of the stool

- Immunoassays to detect cholera toxin directly in the stool

- Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA)

- DNA preparation

- Phage assay

Cholera treatment

Cholera outbreaks are often linked to poor sanitation and lack of access to clean water. To fight the infection, a multifaceted, flexible strategy is needed. General physicians may prescribe oral rehydration solution (ORS) as the primary treatment for cholera. Other treatment approaches below can meet a specific need and help reduce the burden of cholera.

- Rehydration: Oral rehydration therapy (ORT)

- Antibiotics: Macrolides, fluoroquinolones

- Micronutrients: Zinc and vitamin A supplementation in children

- Vaccination: Killed whole-cell (WC) monovalent V. cholerae vaccines with a recombinant B subunit of cholera toxin, killed WC modified bivalent V. cholerae O1 and V. cholerae O139 vaccines without the B subunit, live attenuated oral cholera vaccines (OCVs), parenteral cholera vaccines

- Probiotic treatment

- Phage therapy

FAQs - Frequently Asked Questions on Cholera

Is cholera a communicable disease?

Yes, cholera is a communicable disease. It is a highly contagious diarrheal disease that can spread quickly from person to person through direct, indirect, or droplet contact and affects several people every year

Is cholera a waterborne disease?

Cholera is a severe form of waterborne acute dehydrating diarrheal disease well known for its epidemic and pandemic potential. It is a significant public health concern, mainly in developing countries with inadequate access to potable drinking water and hygienic sanitation.

Is cholera a bacterial disease?

Yes, cholera is a bacterial disease caused by a gram-negative bacterium named Vibrio cholerae. It is usually seen in foods or in water that have been contaminated by feces (poop) from a individual infected with vibrio cholerae bacteria. It is most likely to occur and spread in places with inadequate hygiene and poor sanitation.

Is cholera vaccine contraindicated in pregnancy?

Pregnant women are vulnerable (at risk) to complications of cholera disease. Killed oral cholera vaccines (OCV) are generally not recommended for pregnant women, though there is no proof of harmful effects during pregnancy.

What is the difference between cholera and typhoid?

Cholera and typhoid fever are potentially life-threatening infectious diseases mainly transmitted through the intake of food, drink, or water contaminated by the feces or urine of subjects excreting the pathogen. Cholera is primarily caused by intestinal infection by the toxin-producing bacterium Vibrio cholerae, whereas typhoid fever is mainly caused by Salmonella typhi.

Who discovered cholera?

The microorganism responsible for causing cholera disease was first discovered by Filippo Pacini, an Italian physician, in 1854 during a cholera outbreak in Florence, Italy. Later, Robert Koch discovered it independently in 1883 in India.

Who discovered cholera vaccine?

The first cholera vaccine was developed in 1885 by Ferran and used in mass vaccination campaigns in Spain [Pollitzer and Burrows, 1955; Mukerjee, 1963]. Although variations of parenterally administered killed whole cell (WC) bacterial vaccines have been used before, they have never been recommended by the WHO due to their limited efficacy and short duration of protection.

What is the shape of vibrio cholerae?

Vibrios are curved or comma-shaped, highly motile, gram-negative rods with a single polar flagellum. Vibrio cholerae O group 1, the agent of cholera, is the most important of the vibrios that are clinically significant to humans.

Which parts of the world are most likely to experience cholera?

The home of cholera is around the Bay of Bengal, like Bangladesh and India. Still, cholera now affects most countries of South and Southeast Asia and most countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. The large epidemic in Haiti appears to be over, though it may be too soon to be sure.

What constitutes a cholera outbreak, and when is a country deemed endemic?

An outbreak of cholera occurs when documented cases are seen, and there is evidence of ongoing transmission in the area. Outbreaks may occur in endemic or non-endemic areas. As per the World Health Organization (WHO), countries are said to be endemic for cholera if cholera cases have been reported in three out of the previous five years.

What temperature kills cholera?

If exposed to temperatures of 80-100°C, V. cholerae 01 dies within a few seconds; at 65°C it dies within 10 min. Freezing does not necessarily kill V. cholerae 01, and it can survive long periods in the frozen state. More organisms are destroyed at -2 to -10°C than at -70°C. Drying and sunlight affect V. cholerae O1 unfavorably.

Can cholera survive in soil?

V. cholerae bacteria is excreted in the feces and vomitus. Viable organisms can be seen in feces for up to fifty days, on glass for up to a month, on coins for seven days, in soil or dust for up to sixteen days, and on fingertips for 1 to 2 hours.

Share on

Request an appointment

Fill in the appointment form or call us instantly to book a confirmed appointment with our super specialist at 04048486868

Appointment request - health articles

Popular Articles